Summary:

This long read essay explores "primals"—fundamental beliefs shaping human behaviour—arguing that differing primals, often rooted in both biology and culture, fuel conflict and inequality. It examines the interplay between competition and cooperation, proposing that while innate competitive tendencies exist, cultural evolution can shift societal norms towards cooperation. The essay uses complex systems theory and evolutionary game theory to model this dynamic, highlighting the roles of third-party punishment and the Tit-for-Tat strategy in fostering cooperation. Finally, it integrates Jonathan Haidt's Moral Foundations Theory, suggesting that understanding the interplay between primals and moral foundations can illuminate political polarisation and pave the way for greater cooperation.

Introduction

Humans hold primal beliefs (primals) that drive their behavior. Primals can be described as basic, deeply rooted beliefs about the fundamental nature or characteristics of the world and human existence, shaping perceptions and behaviors. Common primals include views of the world as safe/dangerous, just/unjust, benevolent/meaningful, unpredictable/chaotic, and beliefs about people. They reflect philosophical stances on existence and strategies for navigating life, embodying high-level mental models that often operate unconsciously. Primals are culturally adopted beliefs and emerge from sociocultural patterns of behavior but have biological/evolutionary causes rooted in genetically influenced traits, temperaments and responses.

Importantly, primal beliefs in certain nature of the surrounding world or others are reflected in human behavior and interaction. For example, holding primals that the "world is dangerous" may contribute to persistent negative mental states of anxiety and stress, while believing that the "world is safe" promotes positive, peaceful and stress-free states of mind.

Differences in political orientation seems to be no more than a competition between differing primal beliefs. For instance, geopolitical conflicts are often triggered by antagonism between countries or cultures holding opposing primals. Hence, it could be argued that contrasting and competing primals are among the primary causes of conflict and inequality in present-day human societies. In human interactions, opposing worldviews and ideologies are the cause for consistent conflict between individuals and groups, generating antagonistic moral beliefs and Us-versus-Them mentality within populations. The harsh truth in a societal reality seems to be that when competition is present, cooperation is not possible, and vice-versa. More often than not, the most competitive will succeed at the cost of others: it's a dog-eat-dog world in which only the fittest will survive, and where cooperative efforts are made impossible by defectors and free-riders. Thus, the case could be made that most present-day societies are firmly rooted in competition, because they operate as implicitly competitive top-down hierarchical social structures.

The nature of competition itself implies that there are two or more competing sides, and winners and losers. For instance, in political competition, there are voters that share the primal beliefs of the "winning" side, while those in the "losing" side hold opposite beliefs. Thus, winners always win at the cost of the losers. Crucially, the existence of political competition, and winners and losers, also implies that the existence of cooperative and egalitarian society is simply not possible within today's centralised and hierarchical nation-states. A truly cooperative and egalitarian social organisation may only be realistic within the principles of a direct/participatory democracy (i.e. "power of the people", "one person one vote"). However, today's centralised societies are only superficially and rhetorically "democratic" - currently no country in the world has a direct and fully participatory democracy in place. Rather, all modern self-entitled democracies are governed by hierarchical and authoritarian social organisation systems of representative democracy. Here, the rhetoric fallacy arises: representative democracy is a top-down structure fundamentally rooted in competition and concentration of power in a single authority or a small group, while in contrast, direct democracy is structured from bottom-up as a system based on cooperation and egalitarianism. In the absence of direct democracy, cooperation is also difficult if not impossible - and most societies are fundamentally competitive for the simple fact that they practice politics based on competition.

Here, primals might play a crucial role: achieving a truly egalitarian and participative social organisation may require large-scale changes in primal beliefs within societies, powerful enough to help entire populations to shift their basic beliefs away from competitive worldviews and towards more cooperative primals. Afterall, primal beliefs are often socially and culturally dependent constructs, rather than biological entities - therefore they can be changed.

Changing primals can be difficult for several reasons. Firstly, because primal beliefs are influenced by social environments, changing individual beliefs is difficult due to social and cultural pressures such as commonly adopted cultures, belief systems and social norms. Going against the social norms of the in-group is usually punished by the same in-group, making defection from norms costly for the defector.

Secondly, while under the influence of social environments, primals are fundamentally rooted in evolutionary/biological structure which is often difficult or impossible to change. Behaviors like vigilance, aggression, approach or avoidance stem from biological patterns of threat/safe responsivity, firmly rooted in emotions, which are evolutionary survival mechanisms found in all animal species, shaped and conserved by natural evolution over millions of years.

However, certain sociocultural patterns of behavior arise from cultural evolution and therefore lack the limiting constraints of a biological structure, allowing room for plasticity and change of beliefs, including primals.

Humans can be viewed as a living and self-organizing complex system. From this complex systems perspective, primals can be considered as system's behavior emerging from cybernetic feedback loops between biological structure shaped by evolution (nature) and patterns of behavior emerging from that structure, influenced by biological, developmental, environmental and sociocultural factors (nurture). Nature and nurture interact through cybernetic feedback loop to shape developing primals over the lifespan.

Biological constraints set limits for changing primals but allow for behavioral flexibility within those limits. Complete transformation of primals may not be possible without structural changes - but making changes in genetic structure is hard if not impossible (gene therapies and editing technology such as CRISPR are still in experimental stages, expensive and unavailable for the greater public). In contrast, behavior influenced by cultural evolution, such as certain beliefs and social/cultural constructs, are less constrained by biological structure, allowing more behavioral flexibility for the shaping of sociocultural traits like primals.

Differences in primal beliefs often leads to conflicts, especially between antagonistic socio-cultural groups holding opposing primals. Historically, most socio-cultural conflicts emerge from differences between primals, triggering competition between cultural groups holding opposing political and religious beliefs.

While competition and antagonism may appear normalised in modern societies, a shift to less conflictual societies can be achieved through cooperation and acceptance of diverse primals. The ability for cooperation between and within human groups is one of the hallmarks of our evolution, as cooperation in hunting-gathering and egalitarian lifeways has yielded crucial adaptive fitness, promoting continuity, survival and reproduction of our species.

Human within-species competition emerged as a cultural adaptation and response to change in subsistence model (food production, sedentarism), not inherent biology. Hence, cultural shifts could also reverse it: cultural changes can redirect incentives away from competition towards cooperation. This impacts cultural patterns of behavior first before biological ones, as biological changes occur gradually over generations, while cultural changes can occur and have significant effects within a single generation.

Incumbent competitive powers may resist cultural changes threatening their dominance, but grassroots movements, alternatives models, and multigenerational cultural reform offer some ways to induce changes in primal beliefs. Transforming primals requires long-term, bottom-up changes in cultural evolution given constraints of top-down power structures and gradual nature of biological changes. Over time, successive changes in sociocultural patterns of behavior can impact the underlying biological structure, reinforcing natural selection for cooperation, thus promoting evolution of more cooperative societies.

“Only the individual can think, and thereby create new values for society, nay, even set up new moral standards to which the life of the community conforms. Without creative personalities able to think and judge independently, the upward development of society is as unthinkable as the development of the individual personality without the nourishing soil of the community."

Albert Einstein - from The Theosophy of Albert Einstein

Chapters:

Introduction

Introduction to Primals

Looking at primals from complex systems perspective

The Systems Dynamics of Human Behavior

Determinism or free will? Primals can only be altered so far given biological constraints

Biology of change - from competition to cooperation

Balancing out Competition and Cooperation

The Challenge of Free Riders and the Stability of Cooperation

Third-Party Punishment: One (potential) Solution

The Evolution of Third-Party Punishment

Cultural Evolution and Institutions

Evolutionary Game Theory: Why do humans cooperate?

Tit-for-Tat: Balancing Cooperation and Competition in Evolutionary Game Theory

Competition increased as cultural adaptation

Transition to sedentarism and food production increased competition

Plasticity of adaptations - cultural evolution can be changed by cultural evolution

The Moral Foundations Theory

Cultural Influences on Moral Foundations

Cultural Evolution of Morality and Cross-Cultural Differences

Connecting Moral Foundations to Political Polarization

The shared characteristics of Moral foundations and Primals

Competitive leaders resist changes in society and culture

Conclusion: Reconciling the Forces That Shape Our Realities

Introduction to Primals

Primals are considered to be extremely basic beliefs about the world as a whole. In general, any core assumption about how the world works on a fundamental level or what strategies are best for dealing with existence could be considered a primal world belief. Primals reflect philosophical and motivational stances on the nature of change, social dynamics, and strategies for navigating life. They are deep-rooted high-level mental models for understanding the world and one's place within it. Primals can operate largely outside conscious awareness to influence perceptions and behaviors.

Some common primals:

The world is a dangerous place - The view that the world is fundamentally threatening and full of threats. This tends to promote a more cautious, protective outlook.

The world is benevolent/meaningful - The opposite view that the world can generally be trusted and has meaning or purpose behind events. This view tends to correlate with more openness and optimism.

The world treats people fairly - A belief that good things happen to good people and vice versa, that people generally get what they deserve. This view provides a sense that the world is just.

The world is unpredictable/chaotic - The view that events occur arbitrarily without meaning or cause, and the future cannot be known. This view sees randomness and lack of control over outcomes.

People are generally good - The belief that most people have good intentions and can be trusted. This promotes social engagement and trust in others.

People are fundamentally untrustworthy - The opposite view, that people are often deceptive or self-interested and cannot always be trusted. This view makes interactions more cautious.

There are fixed rules in life - A belief that there are immutable rules or truths that govern life events and human behavior. This provides a sense of structure and predictability.

Future is uncertain, past was safer time - This taps into the "world is unpredictable/chaotic" primal, with an added component that the past offered more stability and certainty compared to the present/future. It promotes nostalgia and reluctance towards change.

Competition is better for survival than cooperation - This aligns negatively with the "World runs on trust and teamwork" primal outlook. It suggests the world is fundamentally competitive, with an every-man-for-himself mentality needed to thrive. This view tends to undermine trust and teamwork as cooperative strategies.

Primal world beliefs are also measurable with psychometrically validated scales. A 99-item survey measuring all 26 primal world beliefs is considered the most accurate measure of primal world beliefs. link

The following diagram explains the structure of primal, secondary and tertiary world beliefs:

Empirical studies have been conducted to investigate the impact of primals in sociocultural, psychological and biological contexts. A 2021 study showed that many parents purposefully aim to instill in their children negative primal world beliefs, especially the belief the world is a dangerous place, assuming that seeing the world as dangerous is tied to health, happiness, and success. But in truth, those who see the world as dangerous are less likely to succeed, tend to have worse health due to stress and anxiety, and experience depression at a higher rate.

Likewise, another study suggests that certain primals, including the belief that the world is hierarchical and the world is just, are linked to political beliefs. Beliefs in political systems, such as democracy or authoritarianism, can be considered primal beliefs, in that political beliefs tend to have a strong character and continuity across lifetime, and even across generations. In certain cultural landscapes, it is quite common that primal political beliefs are transferred through inheritance from the previous generation, from parents to offspring, over decades.

Primal worldviews are often discussed in the context of core beliefs or assumptions as being related to certain cultural norms. Nevertheless, the underlying mechanisms have biological and evolutionary underpinnings as well. Individual differences in threat perception and stress responses to certain stimuli are partly due to biological patterns and traits, shaped by evolution to aid survival and reproduction. For example, some may have an genetically inherited disposition to be more cautious/threat-sensitive, while others have genes that make them more tolerant in response to the exact same stressors. Some attachment styles (e.g. secure vs. anxious) developing in early life also have biological underpinnings and could predispose individuals to see the world as more safe/benevolent vs dangerous. Common human personality traits such as Neuroticism are partly heritable and linked to stronger negative emotions and sensitivity to threat/danger cues from the environment. Primal social mindsets, like competitiveness vs. cooperativeness or individualism vs collectivism, emerge from both genetic dispositions and how these traits were adaptive at different points in humanity's evolutionary past.

So while primals are often discussed at the belief level, the core temperaments, traits and biases that underlie them could be deeply biologically ingrained as well - rooted in patterns emerging from genetics and biological evolution, behaving under the influence of environmental and developmental factors. Both nature and nurture interact to generate one's fundamental assumptions about the social and physical world.

Looking at primals from complex systems perspective

In complex systems theory, cybernetics deals with circular causal systems whose outputs are also inputs. It is concerned with the general principles of circular causal processes, including in ecological, technological, biological, cognitive and social systems. The central theme in cybernetic systems is feedback. Feedback is a process where the observed outcomes of actions are taken as inputs for further action in ways that support the pursuit, maintenance, or disruption of particular conditions, forming a circular causal relationship. For example, in steering a vehicle, the driver maintains a steady course in a changing environment by adjusting their steering in continual response to the effect it is observed as having. In human context, this theme has also been carried forward in modern biocybernetic and psycho-cybernetic theories like Cybernetic Trait Complexes Theory) or Cybernetic Big Five Theory.

Systems dynamics is a method to understand the dynamic behavior of complex systems. The basis of the method is the recognition that the structure of any system, the many circular, interlocking, sometimes time-delayed relationships among its components, is often just as important in determining its behavior as the individual components themselves. It also follows that because there are often properties-of-the-whole which cannot be found among the properties-of-the-elements, in some cases the behavior of the whole cannot be fully explained in terms of the behavior of the parts. These unexpected behaviors emerge from within the dynamics of the system, being described by terms like emergence, non-linear behavior, entropy, or simply randomness.

From this system dynamics angle, primals can be considered as properties of behavior: behaviors/primals are an observable manifestation of behavior of the human cybernetic system. Hence, observing the properties of primals as behavior may provide a new perspective into the dynamics of the feedback loop driving their emergence and expression.

The Systems Dynamics of Human Behavior

The human cybernetic feedback loop is dynamically influenced by both nature and nurture. Here, nature refers to the genetic and biological structure generating patterns of behavior, while nurture refers to the developmental, environmental and social factors that influence these same patterns, ultimately leading to observable behavior. These factors interact with each other in a self-organizing cycle through feedback loops, where each component influences and is influenced by the others. The dynamics within any complex system are non-linear and emergent, meaning that small changes in one component can have a significant impact on the entire system, and that changes in the system emerge over time as feedback from its own dynamic behavior.

The central principle here is that human behavior arises from patterns of behavior, which in turn arise from biological structure. You can't really change patterns of behavior unless you make changes in the biological structure that creates them - and it's extremely hard to change the biological features we're born with. Hence, if the structure can not be changed, any change in an individual's behavior requires changing their patterns of behavior. Some patterns arising from cultural evolution are largely independent from biological structure, therefore can be more readily changed. But while it may be possible to change behavior arising from cultural evolution, it's still much harder to change behavior arising from biological patterns and structure.

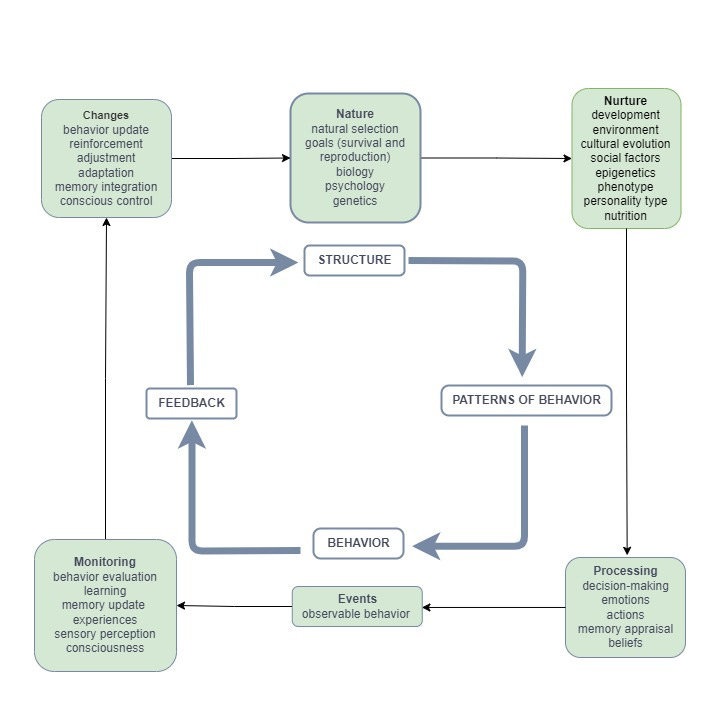

In general theory of complex systems, cybernetic feedback loops between four fundamental "stages" dynamically shape the emergence and updating of behavior. As a defining principle of dynamic systems, causality in each state is explained by the preceding stages:

Structure - Causes the properties of patterns of behavior

Patterns (of behavior) - Behavioral patterns cause behavior

Behavior - Behavior causes feedback

Feedback - Feedback causes changes in behavior, patterns and structure

These principles of cybernetic feedback can also be applied to living dynamic systems, such as humans. In human systems, individuals' genetic makeup and biological structure (nature) establishes certain core temperaments, tendencies, sensitivities, etc. The structure generates a certain range of behavioral patterns (nurture), which in turn yields a certain range of behaviors (events). These behaviors then feed back to previous stages, continuously introducing changes to the system and influencing the update and integration of new behavior.

In human system dynamics, the main role of the cybernetic feedback loop is to maintain the organism operational within optimal range of behavior, through monitoring and regulation of homeostasis (functional balance within living systems). Changes introduced in all other stages of the feedback loop are ultimately expressed as behaviors. These behaviors are again monitored through the system's sensory perception, followed by perceptual inference that results in an adaptive change in different stages of the feedback loop. As a result of this balancing/reinforcing feedback loop, changes that become integrated into the system in multiple stages ultimately lead to changes in the expression of its behavior.

In this cybernetic systems view, both natural evolution and cultural evolution have interacting effects that shape both phenotypic patterns and developing primals through recursive feedback loops over the lifespan. Both genetic predispositions and life experiences collectively influence one's fundamental orientation towards the self and world.

Let us consider the following diagram describing a human cybernetic system:

This diagram illustrates a cybernetic feedback loop where nature (innate traits) and nurture (environmental influences) dynamically shape human behavior. It shows a cycle of four dynamic stages where structure (nature) and patterns of behavior (nurture) influence behavior, which is then subject to feedback/changes, leading back to influence both nature and nurture. In each of these stages, dynamic changes are introduced to the feedback loop resulting in changes in the overall system.

STRUCTURE / Nature: Natural evolution and biological makeup establish the core structural dispositions of human behavior, temperaments, tendencies, sensitivities, etc., creating patterns of behavior.

PATTERNS OF BEHAVIOR/ Nurture: These dispositions influence individual's patterns of behavior and their interactions and responses to their environment (patterns generate behavior).

BEHAVIOR / Events: This is an observable expression of behavior of the system. Expressed behavior emerges from patterns of behavior. Through developmental experiences, individual's patterns of behavior and responses begin to form consistent behavior such as beliefs about how the world works (phenotype impacts primals). Environmental/sociocultural factors also impact behavior through additional life experiences, learning, culture, etc. (nurture shapes behavior).

FEEDBACK / Changes: These behaviors then feed back causing changes to further influence the individual's perceptions, decision-making and behaviors as they navigate life experiences. Through changes caused by feedback, behaviors/primals become recursively reinforced over time. Changes in behavior/primals may also feed back to patterns of behavior.

To understand cybernetic feedback loop in systems dynamics, we look at causation: what causes what in the loop? What changes does the feedback cause in the loop? If the biological structure is not changed some patterns can't change, because patterns of behavior are caused by their structure. For the same reason, if patterns of behavior are not changed, behavior itself can't be changed much either - patterns of behavior cause the behaviors . Nevertheless, it is possible to introduce changes to both the patterns and expression of behavior by generating reinforcing/inhibiting feedback loops, but the effects of feedback are limited to the degree they are constrained by the structure.

Within this framework, the underlying evolutionary/biological structure sets constraints and predispositions that are not easily changed. Given an unchanged structure, core behavioral patterns are also resistant to change and recursively reinforced. Similarly, because primals emerge from patterns of behavior, it is difficult to alter them permanently without structural changes. Behavioral patterns emerging from cultural evolution, such as primal beliefs, can only be altered so far given biological constraints.

Structures strongly constrain the range of possible changes in patterns/phenotypes and behaviors/primals. While behaviors and explicit beliefs/primals can be influenced or modified to some degree through experience/learning, these changes can not change the underlying biological structure. Changes in pattern-level are not permanently integrated or fully eliminate underlying predisposing tendencies, because the core biological structure remains unmodified. The influence of structures in patterns of behavior does have some capacity for plasticity through epigenetics, neuroplasticity, etc. over the lifespan in response to environmental factors. Nevertheless, this plasticity can exclusively affect the dynamics between patterns of behavior and feedback, leaving the underlying genetic and biological structure (that "causes" both the system itself and its dynamics) untouched.

In other words, this complex human systems dynamics view suggests that primals can be situationally influenced, but not permanently transformed without structural change. But then again, major restructuring of human biological structure is not realistic. The greatest potential for change lies in modifying behaviors and responses adaptively within structural constraints through learning, and focusing on behaviors that are sociocultural adaptations.

Determinism or free will? Primals can only be altered so far given biological constraints

Given the strong influence of biologically determined structures, Robert Sapolsky's argument for biological determinism has some validity - we are rather constrained beings. Nature is difficult to change, and even when possible, evolutionary changes happen extremely slowly - over many generations and millenia. Changes introduced to the biological structure in this generation will only result in a tiny effect on the next generation, if any at all.

For instance, even if an individual manages to introduce adaptive mutations to change their genetic structure, they must also reproduce after these changes occur. If reproduction happens before these changes have taken place, they will not - can not - pass over to the next generation. And of course the chances of any genetic change passing to the next generation is only 50% from the get-go, as only one half of the genes from each parent are transmitted to the offspring. Given these and other reasons, it is safe to conclude that large-scale changes in evolutionary and biologic structures are simply not expected or realistic within human lifespan.

However, biological structures also allow for a range of adaptive responses to environmental, sociocultural and developmental influences. While constrained, human systems are not mechanistically determined down single paths in their development. Learning and experiences can modify behaviors within structural limits through exertion of willpower and reflective decision-making, even if complete transformation is unrealistic. Conscious modification of behavioral patterns enables the biological structure to integrate new behavior over time, leading to neural plasticity and new adaptive behavior. Human cybernetic system is capable of learning new adaptive behavior over its whole lifespan.

Conscious reflection and cognitive control give humans some ability to override or redirect more automatic primal tendencies and emotional responses through conscious thinking, facilitating practice of alternative behaviors. Primals can be seen as learned habits - thus can change to the degree any habits can be changed.

Importantly, human sociocultural tendencies are more flexible for change than our biological ones, simply because they lack limiting constraints of biological structure. Likewise, cultures and environments that support development of more constructive primal perspectives (e.g. cooperation) can expand the boundaries of what feels "freely" chosen.

So, while complete free will independent of our nature may be an illusion, we retain some degree of authorship and control over behavioral expression of our primal beliefs through exertion of consciousness and choice-making within our structural constraints. Free will emerges from but does not negate our fundamentally conditioned nature. Human agency arises from a complex system with dynamic structure made of multiple parts, rather than absolute determination or voluntarism. Because primal beliefs are our own constructs, we still have some constructed sense of agency that allows for at least some level of change in our behavior even if complete liberation is unrealistic.

Biology of change - from competition to cooperation

Primal beliefs fundamentally differ between individuals. Common primals are also adopted by groups, as exemplified by ideologies shared by political and religious groups. Antagonism between primal belief systems seems inevitable, leading to conflict between these opposing worldviews. Crucially, antagonism and conflict are caused by primal beliefs in competition.

So, assuming that primal beliefs in competition are a strong causal factor giving rise to human conflicts, then changing those primals could potentially impact the patterns of behavior through cooperation-reinforcing feedback loop, shifting them from competition to cooperation.

However, the question then becomes: if an individual is already born with a biological structure that generates competitive behavioral patterns, is it possible to change this pattern to a cooperative one, including through reinforcing feedback?

A laconic answer to this question would be: partially. If an individual is biologically predisposed towards a more competitive pattern of behavior due to their underlying biological structure, then it would be very difficult to fully transform that phenotype to one of pure cooperation. Given that the biological structure causes the competitive pattern of behavior, the biological structure that would need to change for the pattern to change - which as we've seen would be very difficult.

The competitive tendencies are more strongly constrained by their biological structure in this case. While learning and experience can modify behavior to some degree, the core patterns can not be permanently replaced. At best, through conscious effort and environmentally supported development, individuals can expand their range of behavioral responses to include more cooperative behaviors in certain situations and contexts. But still, the preexisting competitive biases yielding from their nature would still exert some influence and could potentially reemerge under conditions of stress, threat, scarcity or unfulfilled needs etc. Their expressed behaviors may approximate cooperation at times, as behaviors can change temporarily, but the full internalization of cooperation as a dominant behavioral pattern may be unrealistic given the limits of structural change over a lifetime. Within this framework, it would not be truly possible to completely transform an innately competitive behavior into one of inherent cooperation due to the constraining effects of biological structure and predispositions. At best, a hybrid responsive repertoire could perhaps develop.

As a practical example, suppose one half of the population has predominantly competitive patterns of behavior and the other half has cooperative patterns. This pre-dispositional dichotomy presents a rather difficult social dilemma: How could it ever be possible for those two antagonistic populations to reach consensus or social agreement? The challenges of sustaining cooperation and social harmony in a population with diverse primals and survival strategies seem unattainable, for once because neither competition nor cooperation is fully possible unless under condition that everyone collectively competes or cooperates. Resolving this global social dilemma is of the highest importance for humans, as the success of our species depends on how well we cooperate with each other.

Many examples of the challenges for sustaining large scale cooperation can be found in modern-day societies, in which neither collaboration nor cooperation can fully be established due to disagreements and conflicts between opposing worldviews. Crucially, most societal, educational and economic systems tend to promote competitive primal beliefs and ethical values, often at the cost of those with more cooperative values and worldviews. If a population is split between strongly competitive vs cooperative predispositions, reaching consensus may be difficult as their aims and behaviors diverge. Pure competition or pure cooperation across the whole group does not seem realistic given the constraints of biological diversity. But even those with competitive biases can learn to cooperate strategically in some contexts when it provides common benefit.

Hypothetically, establishing stable social and cultural systems that incentivize and promote cultural norms favoring cooperation could provide ways to help override primal differences. Over generations, selectively cooperative cultures may gradually shift their patterns of behavior in a more prosocial direction through socialization effects. But tensions/conflicts between and within populations are also inevitable without major restructuring of human nature. Managing these diverse primal dispositions sustainably is certainly challenging on a societal level. Significant society-level cultural and institutional changes and influences would be needed to facilitate cooperation between competing individuals, groups and populations.

Balancing out Competition and Cooperation

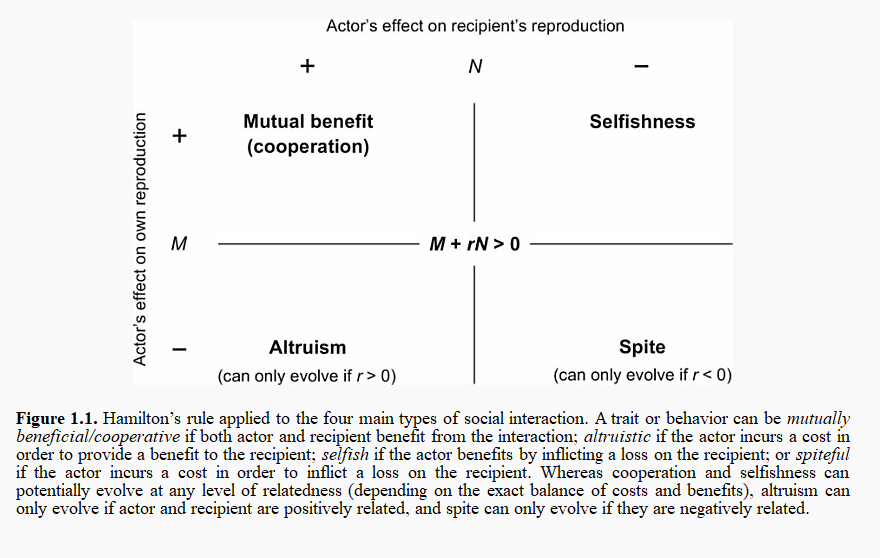

At its core, evolutionary theory posits that traits and behaviors that enhance an organism's fitness – its ability to survive and reproduce – are more likely to persist and spread through populations over time. Competition and cooperation represent divergent adaptive strategies in evolutionary contexts. While competition maximizes individual fitness, cooperation enables collective action and resource pooling, potentially yielding higher average fitness for group members. In this context, both competition and cooperation can be viable strategies: Competition allows individuals to secure resources and mating opportunities, potentially at the expense of others, while Cooperation enables groups to achieve outcomes that would be impossible for individuals acting alone, potentially benefiting all participants.

Importantly, it is not possible to compete and cooperate simultaneously, because the two strategies cancel each other out. When we choose to cooperate, we can not compete, and vice-versa. In any social interaction, the choice must be made between whether we are going to cooperate or compete with one another. Competition occurs between humans for resources, even mates.

Evolutionary game theory provides an interesting framework for analyzing how these strategies interact and evolve. It models social interactions as games, where the success of a strategy depends not just on its inherent qualities but on its performance against other strategies in the population. Aggressive interactions can strongly influence an animal's performance in subsequent contests. Winners of aggressive contests are more likely to win successive contests and losers are more likely to lose successive contests. Such winner and loser effects can significantly influence an animal's dominance status, ability to acquire resources and reproductive success. link. Across taxa, winning increases the odds of winning subsequent fights, while losing increases the odds of losing subsequent fights. The same is also likely to hold true in human animal context.

The Challenge of Free Riders and the Stability of Cooperation

While cooperation can lead to significant mutual benefits for the group and individual alike, it faces a fundamental challenge: the free rider problem. In many cooperative scenarios, individuals can benefit from the cooperative efforts of others without contributing themselves. This creates an incentive to "cheat" or defect from cooperation.

In game-theory, this situation often resembles the famous Prisoner's Dilemma, where the individually rational choice (defection) leads to a collectively suboptimal outcome. If left unchecked, the presence of free riders can destabilize cooperative systems, leading to a breakdown of cooperation and a return to purely competitive interactions.

Empirical evidence from game-theory indicates that a) both institutional rewards and institutional punishment can decrease free-riding and b) that the punishment effect is stronger than the reward effect. Models based on rationality such as Nash equilibrium strategies or evolutionary game dynamics correctly predict which incentives are best at promoting cooperation - but individuals do not play these rational strategies overall.

In human societies, people on average do not react to rewards and punishment, and self-interest and the behavior of others sufficiently explain the dynamics of human behavior. Institutional incentives, such as punishment or reward, promote cooperation by affecting the self-regarding preference and that the other-regarding preference seems to be independent of incentive schemes. Rationally sound strategies are disregarded in favor of consideration of others. Because individuals do not change their behavioral patterns even if they were not rewarded or punished, the mere potential to punish defectors and reward cooperators can lead to considerable increases in the level of cooperation, working simultaneously as deterrent and motivator.

Third-Party Punishment: One (potential) Solution

Enter third-party punishment, an evolutionary concept describing how societies balance these competing forces. Third-party punishment serves as a critical adaptive mechanism, facilitating the emergence and maintenance of large-scale cooperation in human societies. The concept of third-party punishment emerges as a powerful mechanism to address this challenge. It refers to the act of an uninvolved individual (the third party) penalizing someone who has violated social norms or acted unfairly, even when the punisher has not been directly affected by the transgression.

Third-party punishment is crucial for several reasons:

Firstly, it increases deterrence. The threat of punishment from uninvolved parties significantly increases the risk associated with cheating or non-cooperation. This alters the payoff structure of social interactions, making cooperation a more attractive strategy.

Secondly, involvement of an unrelated third party increases norm enforcement. By getting involved and punishing transgressors, third parties actively reinforce social norms that favor cooperation. This helps to create and maintain a cultural environment where cooperation is expected and valued.

Third-party punishment also promotes cost distribution across the system. In systems relying solely on direct reciprocity, victims of cheating bear the full cost of retaliation while cheaters benefit from competing and taking advantage. Third-party punishment distributes this cost among group members, making it more sustainable.

Finally, third-party punishment can be highly effective due to its scalability. As societies grow larger and more complex, direct reciprocity becomes less effective. Third-party punishment allows cooperative norms to scale to larger groups where individuals may not have repeated interactions with every other member.

The Evolution of Third-Party Punishment

For third-party punishment to evolve and persist, it must be able to generate benefits that outweigh its costs. This raises an interesting question to consider: punishing others typically involves some cost to the punisher (e.g., time, energy, risk of retaliation), while the benefits often accrue to the group as a whole. Several theories address how third-party punishment could have evolved:

Group Selection: Groups with effective third-party punishment mechanisms would be more cooperative and potentially out-compete groups lacking such mechanisms. While group selection is controversial in evolutionary biology, recent models suggest it could play a role in human evolution, particularly for culturally transmitted traits.

Reputation Effects: In repeated interactions, which better model real-world social dynamics, third-party punishers may gain reputational benefits. Punishing cheaters signals one's commitment to group norms, potentially leading to more cooperative interactions in the future. This can create a positive feedback loop where the benefits of a good reputation offset the costs of punishment.

Cognitive Adaptations: Some argue that humans have evolved specific cognitive adaptations for third-party punishment. These may include a sense of fairness, moral outrage at norm violations, and the ability to remember and communicate about individuals' reputations.

Models of evolutionary game-theory have demonstrated how third-party punishment can transform social dilemmas. For instance, in a modified Prisoner's Dilemma that includes the possibility of third-party punishment, cooperation can become the evolutionarily stable strategy under a wide range of conditions.

Empirical evidence from experimental economics, anthropology, and psychology supports the importance of third-party punishment in human societies. Economic games like the Ultimatum Game, Public Goods Game or Nash Demand Game with punishment options consistently show that people are willing to incur costs to punish unfair behavior, even when they are not directly affected. Cross-cultural studies have found that third-party punishment is a human universal, though its specific manifestations vary across societies. Neuroimaging studies suggest that observing unfair behavior activates brain regions associated with negative emotions and cognitive conflict, potentially motivating punitive responses.

Cultural Evolution and Institutions

The concept of third-party punishment extends beyond individual-level interactions into influencing the evolution of cultural institutions that codify and enforce social norms.. Societies that develop and maintain effective third-party punishment institutions (e.g., legal systems, regulatory bodies) may be more stable and successful in the long run. These institutions can be seen as formalized, scalable implementations of the third-party punishment concept. They allow societies to maintain cooperation even as they grow larger and more complex, by providing consistent enforcement of social norms through deterrence. When breaking societal rules or laws is likely to lead to negative consequences for the perpetrator, such actions are perceived to represent high risk, serving as a deterrent for transgressions.

Third-party punishment serves as a critical mechanism for balancing competition and cooperation from an evolutionary game theory perspective. It helps resolve the tension between individual self-interest and group benefit by creating an environment where cooperation becomes a more evolutionarily stable strategy.

By deterring foul play, stabilizing cooperative norms, and distributing the costs of norm enforcement, third-party punishment allows societies to enjoy the benefits of cooperation while mitigating its vulnerabilities. This delicate balance has likely played a crucial role in the evolution of human sociality, allowing us to form the large-scale cooperative groups that characterize our species.

Evolutionary Game Theory: Why do humans cooperate?

Understanding how cooperation evolves among humans poses a profound conceptual challenge. On the surface, cooperating initially seems disadvantageous according to the logic of game theory. For example, the theory of Prisoner's Dilemma shows that any individual who makes the first cooperative gesture puts themselves at a strategic deficit, as defection yields a higher reward no matter what the other chooses.

However, while some of the explanatory models of game theory may apply to some non-human species, they do not fully translate to the unmatched scale of cooperation strategies exhibited within human societies. Humans display a remarkable propensity for collaboration even amongst unrelated strangers. We constantly perform small voluntary acts of cooperation and altruism without expectation of direct reciprocation - holding doors, queueing orderly, donating for charities, tipping for services and so on. On a grander scale, humans establish gigantic cultural constructs involving millions of individuals all synchronizing their behavior according to shared beliefs, norms and conventions. Clearly, these manifestations can not be simple developmental/environmental features and more sophisticated evolutionary mechanisms must be at play to account for this phenomenon.

Understanding how and why human cooperation evolved poses a multidimensional puzzle. At first glance, the logic of the Prisoner's Dilemma presents a disheartening perspective - any individual who makes the initial overture towards cooperative behavior puts themselves at a disadvantage. However, closer examination reveals several potential mechanisms for cooperation to take root.

One possibility involves isolated founder populations, where reduced genetic diversity elevates degrees of relatedness. Within this insular environment, kin selection can flourish as cooperation benefits similar genes. Should this pioneering group then reconnect with the wider population, their ingrained collaborative tendencies would outcompete less cooperative outsiders, propagating the behavior on a larger scale.

Another potential factor is the intriguing phenomena of "green beard effects" - where a visible genetic trait coincides with cooperative predispositions directed towards others exhibiting the same marker. In such a scenario, lacking the trait would place individuals at a competitive disadvantage, selectively pressuring the evolution of cooperation. Evidence demonstrates green beard mechanisms operating across diverse species, so they are most likely to operate in humans also.

Several cognitive and psychological mechanisms are woven together to facilitate widespread human cooperativeness. Consider how open-ended interactions, without a fixed termination point of encounters, generate "the shadow of the future" where long-term mutual benefits outweigh temporary gains from defection. Concurrent participation in different social dilemmas, where one has a lower barrier to establishing trust, allows psychological crossover effects that spread cooperation. In other words, while competition may be a better option for a single encounter, cooperation is better for a long run. Win a battle, but lose the war.

Perhaps most insightful is the role of reputation in openly demonstrated past behaviors. Knowledge of another's previous cooperation or selfishness acts as a powerful incentive. On a grand scale, societal norms function like an eternal "reputation book" scrutinized by all. Even amongst hunter-gatherers, gossip circulates reputations, incentivizing helpfulness and cooperation.

Another remarkable example of use of reputation in egalitarian hunter-gatherer societies is the use of ridicule and the practice of demand-sharing. When an individual possesses more resources than they can immediately consume, others can demand the excess resource to be shared with them. If the demand is refused, the whole community will ridicule the person for being a non-sharer and seeker of individual wealth, consequently shattering their reputation and ruining their opportunities for future cooperation with all members of the community - nobody wants to cooperate with a non-sharer. In hunter-gatherer groups, this usually means the ousted individual may need to leave to find another group or face almost certain death, as surviving alone is extremely unlikely. Hence, through the practice of demand-sharing, egalitarianism is imposed by the society on all of its members, securing everyone equal access to resources and wellbeing.

Most elegant of all is how human cooperation evolves into sophisticated "indirect reciprocity" - where Person A assists B, who aids C, and so on. No longer transactional barter, this pay-it-forward reputation system mirrors the fluidity of currency binding vast societies. Through a myriad of transactional mechanisms, humans are highly capable of cooperation even on a large scale.

Tit-for-Tat: Balancing Cooperation and Competition in Evolutionary Game Theory

Across an evolutionary space-time, organisms and systems must constantly navigate the fine balance between cooperation and competition. This fundamental tension, which shapes everything from microbial interactions to human societies, finds a fascinating expression in the realm of game theory, particularly through the lens of the Tit-for-Tat strategy. This deceptively simple approach to decision-making in repeated interactions has profound implications for our understanding of how cooperation can emerge and persist in a world often characterized by self-interest and conflict.

At its core, the Tit-for-Tat (TFT) strategy, first introduced by Anatol Rapoport and popularized through Robert Axelrod's groundbreaking tournaments, follows an elegantly straightforward rule: begin by cooperating, and then in all subsequent interactions, simply mimic the opponent's previous move. This uncomplicated algorithm encapsulates several key features that contribute to its remarkable success and resilience in various scenarios.

The strategy's initial cooperative stance embodies a principle of "niceness," avoiding unnecessary conflict and setting a positive tone for the interaction. However, this is not naive cooperation; TFT's readiness to retaliate against defection serves as a clear deterrent against exploitation. Crucially, this retaliation is balanced by an equal readiness to forgive, returning to cooperation as soon as the opponent does so. This combination of firmness and forgiveness creates a clear and predictable pattern of behavior that opponents can easily understand and respond to.

To better illustrate how TFT affects competition-cooperation dynamics, let's consider a simple example of two neighboring farmers. Farmer A and Farmer B both need to decide whether to cooperate by sharing resources and labor or to compete by hoarding resources and undercutting each other's prices. If both farmers employ a TFT strategy, their interaction might unfold as follows:

Year 1: Both farmers start by cooperating, sharing equipment and helping each other during harvest. This mutual cooperation leads to increased productivity and profit for both.

Year 2: Encouraged by the previous year's success, both continue to cooperate, further cementing their beneficial relationship.

Year 3: Farmer B, tempted by short-term gain, decides to defect by refusing to share equipment. Farmer A, following TFT, retaliates by withholding labor during B's harvest.

Year 4: Farmer B, realizing the negative consequences of defection, returns to cooperation. Farmer A, adhering to TFT, also returns to cooperation, restoring the mutually beneficial arrangement.

This example demonstrates how TFT can enable long-term cooperation while providing a mechanism to protect against and discourage exploitation. The strategy's clarity allows participants to quickly understand the consequences of their actions and the benefits of sustained cooperation.

From an evolutionary perspective, TFT's success is particularly intriguing. In Axelrod's famous computer tournaments, where various strategies competed in iterated rounds of the Prisoner's Dilemma, TFT emerged as the overall winner, outperforming more complex and seemingly sophisticated approaches. This success can be attributed to several factors that make TFT robust in evolutionary terms.

Firstly, TFT performs well against a wide variety of strategies. Against always-cooperate, it engages in mutually beneficial cooperation; against always-defect, it limits its losses after the initial interaction. This versatility allows TFT to accumulate high scores across diverse opponents, a crucial factor in evolutionary success.

Moreover, while TFT is not strictly an Evolutionary Stable Strategy (ESS) in all scenarios, it can achieve evolutionary stability in populations where interactions are sufficiently likely to be repeated. This is because the strategy's ability to retaliate against defection while readily returning to cooperation creates an environment where cooperative behaviors can flourish without being exploited.

The concept of invasion resistance further underscores TFT's evolutionary significance. A population predominantly employing TFT can effectively resist invasion by more aggressive strategies. While such strategies might initially gain an advantage through exploitation, the retaliatory nature of TFT quickly negates this advantage, making sustained invasion difficult.

To understand this dynamic, consider a population of businesses in a marketplace. If most businesses follow a TFT-like strategy of fair pricing and ethical practices, a new entrant attempting to gain market share through predatory pricing and unethical behavior might see initial success. However, as other businesses retaliate by matching the low prices or exposing the unethical practices, the aggressive strategy becomes unsustainable, protecting the cooperative norm.

The success of TFT in fostering cooperation extends beyond pairwise interactions. In many evolutionary simulations, populations employing TFT often outperform those using more exploitative strategies over the long term. This collective success demonstrates that under certain conditions, strategies promoting conditional cooperation can be more evolutionarily advantageous than pure competition.

However, it's important to recognize that TFT is not without limitations, such as its sensitivity to noise or misunderstandings. In environments where actions can be misinterpreted or information is imperfect, TFT can lead to prolonged cycles of retaliation. Imagine two countries following TFT in their diplomatic relations. A misinterpreted action or a rogue element causing a seemingly hostile act could trigger a cycle of retaliation, potentially escalating into sustained conflict despite both parties' initial intention to cooperate. In contrast, if this retaliation cycle is interrupted at any point and both parties cease retaliation, this leaves the door open for the restoration of their relations

Nevertheless, while TFT's simplicity is often an advantage, it can also be a limitation. More sophisticated strategies can potentially exploit TFT's predictability in certain scenarios. Additionally, in multi-player games or complex ecosystems, the effectiveness of TFT can diminish, as it's primarily designed for repeated two-player interactions. Recognizing these limitations, researchers have proposed several variations to address TFT's weaknesses. Generous TFT, for instance, occasionally cooperates even after a defection, helping to break cycles of retaliation in noisy environments. The Pavlov strategy adapts based on the payoff of the previous round, potentially outperforming TFT in some scenarios. These variations demonstrate the ongoing evolution of cooperative strategies in game theory, reflecting the dynamic nature of real-world interactions.

Overall, the Tit-for-Tat strategy, viewed through the lens of evolutionary game theory, provides profound insights into the delicate balance between cooperation and competition. Its simplicity belies a deep relevance to understanding how cooperative behaviors can emerge and persist in competitive environments. Whether in microbial populations or international relations, the principles embodied in TFT – starting with cooperation, reciprocating both positive and negative actions, and being clear in intentions – provide a powerful framework for navigating interactive landscapes.

The global challenges that increasingly require cooperation on unprecedented scales, the theory of TFT and its variations become ever more pertinent. They exemplify that successful long-term strategies often involve delicate and nuanced approaches to cooperation and competition, where the willingness to collaborate is balanced with the capacity to protect against exploitation. In this way, TFT not only illuminates evolutionary dynamics but also helps navigating strategies in business, diplomacy, and social policy.

Competition increased as cultural adaptation

Before sedentarism and civilisations emerged in the early neolithic around 10.000 BCE, hunter-gatherer societies were largely cooperative and non-competitive. Even modern hunter-gatherer societies are generally distinguished from farmers and pastoralist tribes by their high levels of cooperation, sharing, and an egalitarian social structure with very little direct within-group competition for resources. Most of the remaining HG societies, such as the Hadza, San/Ju'hoansi or Mbendele BaYaka in Africa, can be observed to practice egalitarianism and cooperative social organisation, largely absent competitive practices and patterns of behavior. This exemplifies how, in a modern context, it might be realistic to sustain cooperative societies where within-society competition is absent or extremely rare.

So it is clearly possible for a human population to sustain itself cooperatively without significant competitive pressures, at least under certain environmental conditions - these are likely complex, nuanced tendencies that depend highly on social and cultural context. But like all culturally-dependent behaviors of the system, these behaviors can be changed. Indirect reciprocity and Open-book play are some potential mechanisms capable of inducing changes in both culturally and biologically-dependent behaviors of the system. Both of these strategies are evolutionarily grounded on cooperation and are being employed across species.

Additionally, hunter-gatherer examples show the potency of social and cultural influences in shaping behaviors away from competition, even for those with some innate competitive tendencies. Acceptance and promotion of cooperative primal beliefs like egalitarian sharing, consensus decision making, absence of hierarchies, collective child rearing etc. can minimize competitive drives even in individuals with those predispositions. So perhaps purely cooperative, non-hierarchical societies without significant internal conflict are realistic models that have been observed in our species' history.

Because the hunter-gatherer subsistence model is based on cooperation, the very concept of intra-species competition in human societies must have emerged as a by-product of transformation to farming and sedentarism only from the neolithic onwards. So competition can be understood as a pattern of cultural adaptation that over time influenced naturally emerging behavioral patterns.

But perhaps a provocative question here that gets to the heart of the interplay between biological and cultural evolution is: did the emergence of competition (as a cultural adaptation) change the biological structure itself, or did it simply change cultural patterns of behavior without affecting the underlying biological structure?

It does seem reasonable to postulate that increased competition emerged as a cultural adaptation to pressures of sedentism/agriculture during the Neolithic, and may have provided evolutionary advantages. Over many generations, certain competitive cultural practices (authoritarianism, inheritance, private property, status, social norms etc.) could potentially influence biological evolution by altering selection pressures. For example, more competitive behaviors may have provided advantages for accrual of resources/status to enhance survival and reproductive success. So the long-term practice of competition through social learning and transference could conceivably feed back to gradually influence the biological population structure in a more competitive direction.

However, it's highly doubtful complete biological restructuring of neural/physiological traits occurred over just a few thousand years of this cultural shift. More likely, culture altered the relative costs/benefits of different pre-existing tendencies within a population.

So, cultures do have the capacity to evolve behaviors that then feedback into the gene pool over generations. But competition seems to have originated more as a context-dependent cultural adaptation, rather than hard-wired biological imperative. The interplay between the two forms of evolution is complex with influence flowing in both directions.

Transition to sedentarism and food production increased competition

Taking this perspective further: human hunter-gatherer societies were predominantly peaceful, cooperative and egalitarian, with little innate biological predisposition toward competition. But, there were dramatic changes in human ways of subsistence in the early Neolithic, as some humans transitioned from nomadic to sedentary lifestyle, shifting their primary way of subsistence from hunting/gathering to producing their food. As food production began, so did competition over access to it, and generally over resources. The agricultural revolution and sedentary lifestyle led to new pressures around scarcity of resources like land and stored food. This cultural/environmental shift incentivized competitive behaviors as an adaptive way to survive and reproduce under new conditions of resource competition. Ultimately, cultural adaption resulted in a sudden and dramatic change - from collaborative sharing of infinite resources to competition over finite resources.

As having individual possessions and property became common in these early sedentary societies, it also created social classes and hierarchical social organisation - leading to the arrival of a novel need for competitive behavior. Under these social pressures, individuals increasingly ceased cooperating and began competing for survival. Over generations, competitive cultural practices like private property, social status, inheritance, etc. could have gradually influenced the biological population structure to favor more competitive traits. This is the competitive society we see today. Today's highly competitive nature of many societies reflects the deeply entrenched cultural and socioeconomic systems that still incentivize such behaviors for survival/success in those contexts.

But the core competition phenotype emerged first as a flexible cultural adaptation to new social and economic conditions associated with food production and sedentism. In many ways, this perspective reconciles the biological and cultural influences - competition arose culturally but its long-term practice reciprocally shaped human evolutionary trajectories over millennia.

Plasticity of adaptations - cultural evolution can be changed by cultural evolution

A logical insight we may draw at this point is that because competition first emerged as a culture-driven adaptive response to environmental/social changes, it can also be influenced and changed by cultural evolution.

Culturally structured adaptations are typically more vulnerable to changes than biologically structured ones, because they are under stronger reinforcing influence of cybernetic feedback loop. While both adaptations can be considered as patterns of behavior, it is still relatively more plausible to induce changes to sociocultural patterns than to biological patterns. Cultural behaviors like primal beliefs are generally under heavier selection pressures from developmental and environmental factors than biological patterns. In modern environments cultural practices, institutions, norms, etc. have powerful influence over which behaviors are incentivized vs discouraged.

On the other hand, since the very nature of primal beliefs is subjective and metaphysical, it follows that they can be changed both individually and in groups. This is demonstrated by the existence of cultural differences in religions and belief systems. In modern context, the diversity of primal beliefs is remarkable in urban environments, as multiple belief systems often coexist within the same multi-cultural environment. Furthermore, individuals can willingly reject or reinforce their beliefs, and freely change their ideological convictions multiple times over. This supports the notion that culturally evolved primal beliefs have more plasticity than behaviors rooted in biological patterns.

Within the boundaries of this plasticity also lies one key mechanism to introduce changes in primal beliefs. For example, by culturally promoting alternative worldviews/primals that stress cooperation, equality, sharing, empathy etc., societies could redirect the cultural incentives away from competition. Just as long-term competitive culture likely altered human evolutionary pathways, a sustained cultural shift towards cooperation could gradually influence biological structures over generations. If the primal beliefs were culturally changed to support cooperation, the resulting feedback would first impact cultural phenotype and then over time, it might also partially change their biological patterns or even structure. Individuals with innate competitive tendencies could still behave cooperatively within a cultural system that rewards such behavior. And their descendants may exhibit relatively weaker competitive predispositions due to this cultural-genetic feedback process.

So in essence, cultural changes aimed at cooperative values have real potential to ultimately transform human societies and their structural tendencies in a positive direction long-term. Cultures do have agency and their influence on our behavioral patterns and traits should not be underestimated.

The Moral Foundations Theory

Jonathan Haidt's Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) is a social psychological framework that aims to explain the origins and variations in human moral reasoning. The theory proposes that morality is based on innate, modular foundations that have evolved over time as adaptive responses to various challenges in human social life. It argues that these moral foundations evolved to promote cooperation and social cohesion in groups. Haidt's theory initially identified five moral foundations, later expanded to six:

Care/Harm: This foundation is rooted in our evolutionary history as mammals with attachment systems. It underlies virtues of kindness, gentleness, and nurturance, and is triggered by signs of suffering or vulnerability.

Fairness/Cheating: Based on the evolutionary process of reciprocal altruism, this foundation is concerned with justice, rights, and proportionality. It's triggered by cooperation, cheating, and deception.

Loyalty/Betrayal: This foundation stems from our tribal history and the ability to form coalitions. It's associated with patriotism, self-sacrifice for the group, and is triggered by threats or challenges to the group.

Authority/Subversion: Shaped by our primate history of hierarchical social interactions, this foundation underlies virtues of leadership and followership. It's triggered by signs of dominance and submission.

Sanctity/Degradation: This foundation is related to the psychology of disgust and contamination. It underlies notions of living in a more noble or elevated way and is often associated with religious concepts of purity.

Liberty/Oppression: Added later to the theory, this foundation is concerned with feelings of reactance and resentment towards those who dominate and restrict liberty. It's associated with autonomy and resistance to oppression.

MFT suggests that these foundations are innate and universal across cultures, though their expression may vary. While the foundations are universal, cultures build different virtues, narratives, and institutions upon them, leading to moral diversity. People differ in how much they prioritize each foundation, which influences their moral and political views: Liberals tend to prioritize Care, Fairness, and Liberty, while Conservatives generally value all six foundations more equally, including Authority, Loyalty and Sanctity.

Each of these foundations provided different adaptive advantages in navigating the social and physical challenges faced by our ancestors. Together, they formed a comprehensive moral system that promoted both individual and group survival in the ancestral environment. The varying emphasis different individuals and cultures place on these foundations helps explain moral diversity across human societies.

“The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion,” Haidt 2012

The six moral foundations differ in their adaptive advantages:

Care/Harm:

The Care/Harm foundation developed through the protection of children—our ancestors cared for their children and helped them avoid harm in hopes of witnessing the survival of their genes in future generations. For example, the Care/Harm foundation is seen in contemporary politics when Liberals put a “Save the Refugees” bumper sticker on their car or when Conservatives do the same with a “Wounded Warriors” sticker. These are causes that interest us because we care about the individuals involved and wish for them to avoid harm. Interestingly, Liberals rely more on the Care/Harm foundation than Conservatives—this is evident in Liberal critiques of “heartless” Conservative policies on healthcare, education, or government spending.

This foundation evolved from the adaptive challenge of caring for vulnerable offspring. It underlies virtues of kindness and compassion, and helped ensure the survival of human children who require extended care. The adaptive advantage was protecting and nurturing vulnerable individuals, especially kin.

Fairness/Cheating:

The Fairness/Cheating foundation evolved through self-interest and reciprocal altruism. All organisms are self-interested, but once our ancestors developed the ability to remember past interactions, they could perform altruistic deeds with the expectation of a returned favor. They could also enforce consequences for a violation of such trust. Today, the Liberals demonstrate the Fairness/Cheating foundation when discussing social justice—think of debates about economic inequality in which Liberals argue that the wealthy are “not paying their fair share.” The Conservatives demonstrate the Fairness/Cheating foundation when it argues that the government takes money from hardworking Americans (through taxes) and gives it to lazy people (on welfare and unemployment) and illegal immigrants (through healthcare and education). When speaking about fairness, Liberals are generally alluding to equality while Conservatives are generally alluding to proportionality. Hence, the disconnect—at least in part. Nevertheless, Liberals still rely more on the fairness foundation than Conservatives.

This foundation is rooted in the evolutionary process of reciprocal altruism. It helped humans reap the benefits of two-way partnerships while avoiding exploitation. The adaptive advantage was fostering mutually beneficial cooperation and protecting against free-riders.

Loyalty/Betrayal:

The Loyalty/Betrayal foundation developed as our ancestors addressed adaptive challenges in coalitions. Loyalty to the group, and hence survival, was favored evolutionarily. Today, the human predilection for in-group loyalty remains and accounts for a large part of the political “us versus them” divide. The Right relies on the Loyalty/Betrayal foundation when framing debates in terms of nationalism, such as the recent debate about NFL players kneeling for the national anthem. Generally, Conservatives express this foundation more than Liberals.

This foundation stems from our tribal history and the ability to form cohesive coalitions. It promoted group cohesion and cooperation. The adaptive advantage was strengthening group bonds to compete against rival groups.

Authority/Subversion:

The Authority/Subversion foundation was also developed in our tribal pasts. For a tribe to survive, a societal structure had to be established with a leader and followers. In politics today, the Authority/Subversion foundation applies to traditions, institutions, and values. It is more natural for Conservatives to rely on this foundation than Liberals, who define themselves in opposition to hierarchy, inequality, and power.

Shaped by hierarchical social interactions in our primate history, it allowed for beneficial leader-follower dynamics and social order. The adaptive advantage was creating stable social hierarchies and smooth group functioning.

Sanctity/Degradation:

The Sanctity/Degradation foundation was developed through the adaptive challenges of avoiding pathogens, parasites, and other existential threats originating from physical touch or proximity. Judged on a scale from neophilia (an attraction to new things) to neophobia (a fear of new things), Liberals score much higher for neophilia (for food, people, music, ideas) than Conservatives, who prefer to stick with what is tried and true, guarding boundaries and traditions. Social Conservatives particularly rely on the Sanctity/Degradation foundation when discussing the sanctity of life (in the abortion debate), the sanctity of marriage (in the gay rights debate), and the sanctity of self (in the contraception debate).

Related to the psychology of disgust and contamination. It helped humans avoid pathogens, parasites, and other health threats. The adaptive advantage was disease avoidance and promoting health-preserving behaviors.

Liberty/Oppression:

Through a later work, Haidt added a sixth moral foundation: the Liberty/Oppression foundation. Like the Authority/Subversion foundation, the Liberty/Oppression foundation evolved from the dynamics of group behavior, and it views authority as legitimate only in certain contexts. Both sides flex this foundation frequently. The Liberal relies on it in critiques of the wealthy, such as Occupy Wall Street, and in favor of those they view as victims and powerless groups. The Conservative flexes it in a more parochial way, concerned with the specific groups to which they belong. Conservatives say, “Don’t tread on me,” to Big Government in response to high taxes. They extend the argument to the spheres of business and nation, objecting to regulatory policy and international treaties, such as those created by the United Nations.

This foundation deals with feelings of reactance against domination. It helped individuals resist bullies and tyrants. The adaptive advantage was protecting against overly dominant individuals and maintaining personal autonomy within the group.

Cultural Influences on Moral Foundations

Culture plays a significant role in shaping and expressing moral foundations. While MFT proposes that the moral foundations are innate and universal, cultures build different virtues, narratives, and institutions upon these foundations. This leads to moral diversity across societies.

Haidt and Joseph argue that each moral foundation forms a cognitive module whose development is shaped by culture. They suggest that these modules provide "flashes of affect" when certain patterns are encountered, but cultural learning processes shape individual responses to these flashes.

Different cultures place varying emphasis on each of the moral foundations. This variation in emphasis contributes to the diverse moral landscapes observed across societies. Cultures utilize the "building blocks" provided by the moral foundations differently, and this differential use of the foundations results in divergent moralities across cultures.

Some scholars argue that morality is "thick from the beginning, culturally integrated, fully resonant." When we find commonalities across cultures, these may be "reiterated features of particular thick and maximal moralities".

Furthermore, emergent phenomena such as languages, religions, governments, and communities play a crucial role in shaping moral concerns. These institutions, while created by humans, take on lives of their own and profoundly influence moral judgments. For instance, studies of when and why people blame victims for their own suffering have found that the more people express strong support for moral values centered on authority and traditional hierarchies, the more likely they are to agree that victims deserve their misfortune. The findings also suggest that the more people express support for moral values centered on care and fairness, the more sensitive they are to victims’ suffering. Such values can be consciously cultivated and are highly prized by many different communities. These findings apply across different political groups, genders and religious beliefs. Link

Cultural Evolution of Morality and Cross-Cultural Differences

Members of traditional, collectivist societies tend to be more sensitive to violations of the community-related moral foundations (Loyalty, Authority, Sanctity). In contrast, members of WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) societies are more individualistic. Haidt's initial fieldwork showed that moralizing varies among cultures, but differences based on social class (e.g., education) and age were often more pronounced than cultural differences.

Within cultures, political ideology correlates with different emphases on moral foundations. For example, in Western contexts, conservatives tend to value all six foundations more equally, while liberals prioritize Care, Fairness, and Liberty.